Daffy Duck

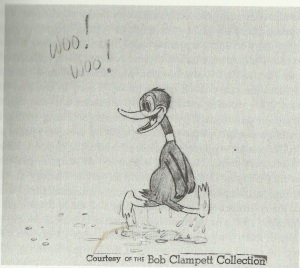

“He was essentially an early thirties rubber-hose design (not a full anatomical character) – mostly two circles attached by a cylindrical neck, inked entirely in black, not much volume, mostly skin without bones. In early cartoons, he would pull his skin back to show he was just skin and bone, but there would be no clear sense of an anatomy inside.”

“He was virtually dematerialized, able to hop across water as if he had no weight whatsoever, or the water were simply a drawing. On various cels, he was also inked with a blur along his back, one of many devices [Tex] Avery used to accelerate sudden bursts of speed. Slowed down on moviola to one cel at a time, these blur drawings suggest a body disintegrating under its own momentum, or a body intentionally incomplete, as if part of the outline were missing.

There were advantages to being boneless and incomplete. Daffy was designed to move as improbably as possible, the first of many such characters that Avery developed – enigmas who lived outside the rules of plot, space, and time.”

Norman M. Klein – 7 Minutes. The Life and Death of the American Cartoon.